How apt update works

- Published on

- Utkarsh Chourasia--7 min read

Have you ever wondered why you need to run apt update before apt install <package> on a Linux system? How does the system know where to fetch the <package> from?

This article explores how apt update works.

The overall concept is similar across other package managers like

yum,dnf, orzypper, although the specific commands and implementation details may vary.

What is apt ?

apt stands for Advanced Packaging Tool. It is the default package manager found in Debian and Debian-based Linux distributions such as Ubuntu and Kali. At its core, apt is used to manage software packages — allowing you to install, update, upgrade, and remove them with simple commands.

Under the hood, apt acts as a high-level interface to the lower-level tool called dpkg (Debian Package Manager), which directly handles .deb files — the archive format used for Debian software packages.

Think of dpkg as a tool that knows how to install or remove a package file locally, while apt knows how to fetch those packages from remote repositories, resolve dependencies, and maintain your system’s package index.

To use an analogy: if .deb files are like .zip archives, then dpkg is like unzip, and apt is like a package-aware downloader that knows where to find the right .zip files and how they all fit together.

To get a feel for what’s happening under the hood, I highly recommend starting your own Debian-based container and following along.

docker run --rm -it ubuntu:20.04 # Start a fresh Ubuntu container

Running apt install before apt update

I’m going to use vim as the example package for this tutorial because it depends on several other packages. That makes it a good candidate to observe how apt handles dependencies during installation.

Let’s try to install vim right after starting our container:

$ apt install vim # First command, as soon as I enter the shell.

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree

Reading state information... Done

E: Unable to locate package vim

You ran apt install vim, but it threw an error:

E: Unable to locate package vim.

Why? Because the system doesn’t yet know anything about a package named vim.

The fresh container we launched is like a newborn baby — it doesn’t know what software packages are available out there. It has apt, but no package index to search through.

That’s where apt update comes in. When we run apt update, we're essentially telling the system:

“Here’s a list of all available packages from your configured repositories — now you can start looking things up.”

Package Index

A package index is like an Oxford Dictionary. It’s alphabetically sorted and maps each package name to its metadata: version, dependencies, maintainer, and more. apt uses this index to locate and install the correct packages.

We’ll look at how this file works soon.

Running apt update

Running apt update will download the latest index.

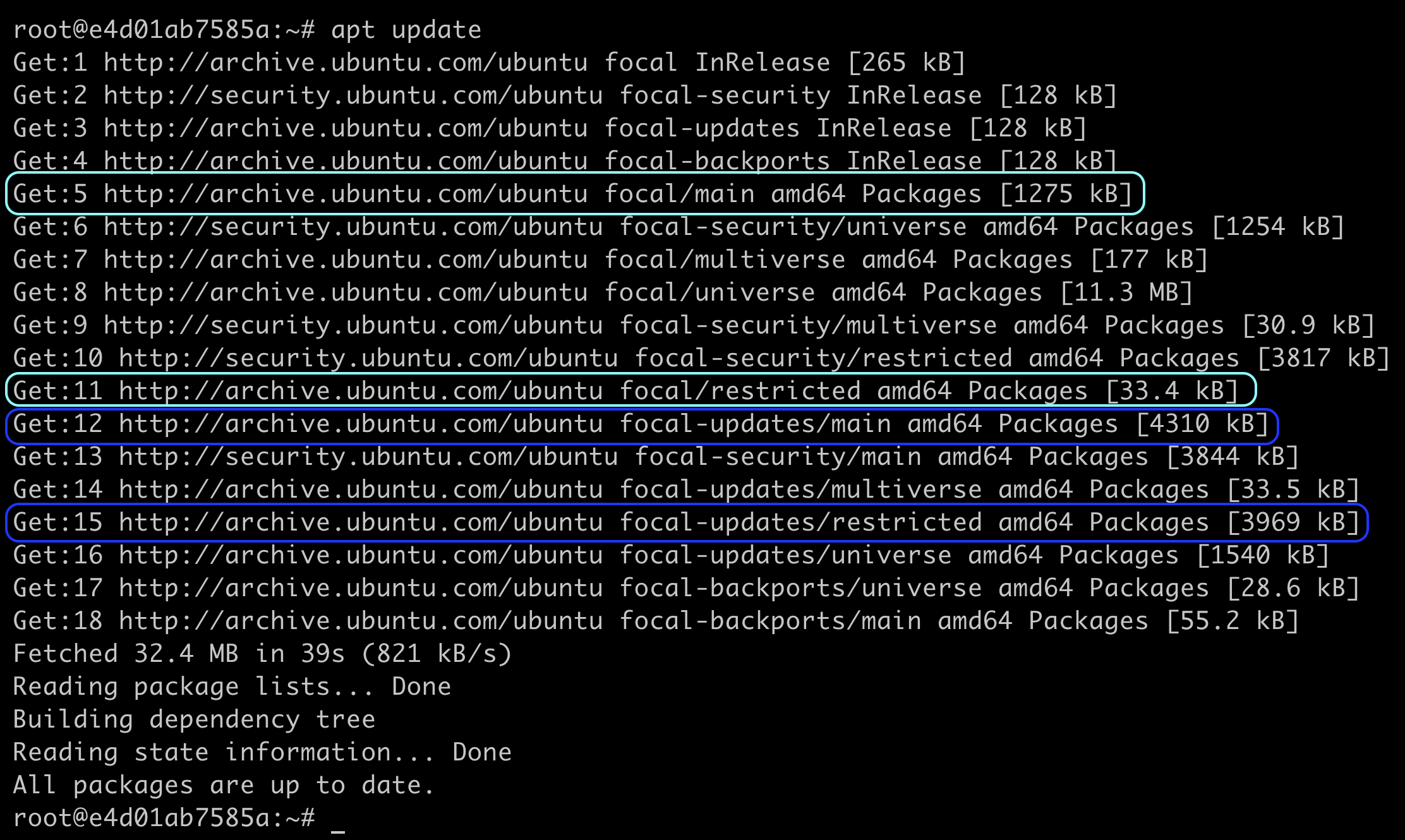

As you can see above, apt update is downloading 18 index files.

But wait — how does the machine know where to fetch these indexes from?

This is a fresh container, and we didn’t specify any repository URL. So where is apt getting this information?

The source of truth

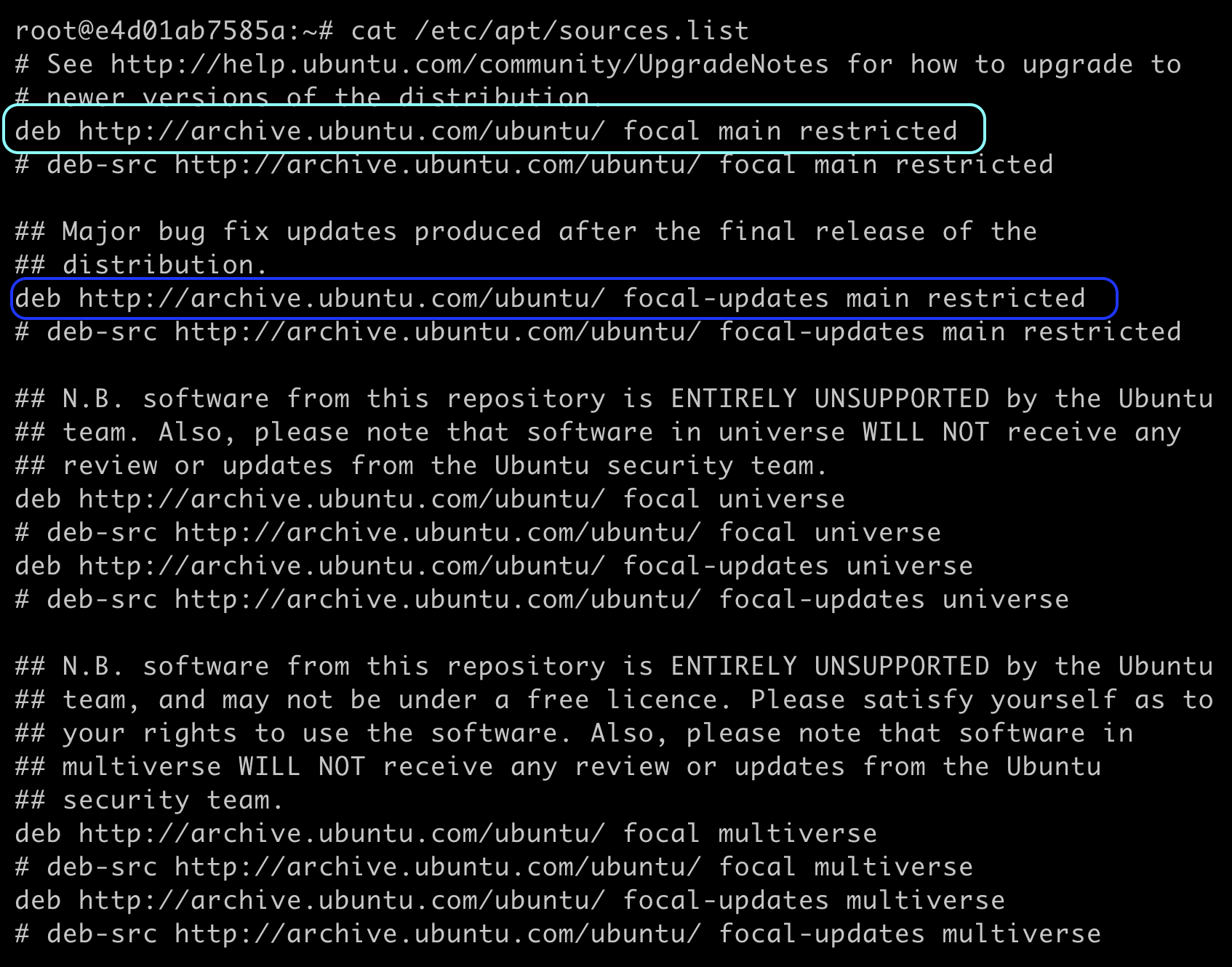

Just like (living) organisms have DNA that carries genetic information for development and functioning, a container or virtual machine has its own “DNA” in the form of configuration files. One such file is /etc/apt/sources.list, which defines the locations (URLs) from where packages and index files are retrieved.

If you compare this file with the output from apt update, you’ll notice many matching keywords and URLs (see the colored rows in both screenshots). That’s because apt reads this list to know where to fetch package indexes and actual .deb files from.

Here's the breakdown of the deb format:

-

Archive Type (e.g.

debordeb-src)debrefers to pre-compiled binary packages — the.debfiles that get directly installed.deb-srcrefers to source packages. These can be downloaded and compiled locally if needed.

-

Repository URI This is the web address (e.g.

http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/) pointing to the server hosting the package indexes and.debfiles. -

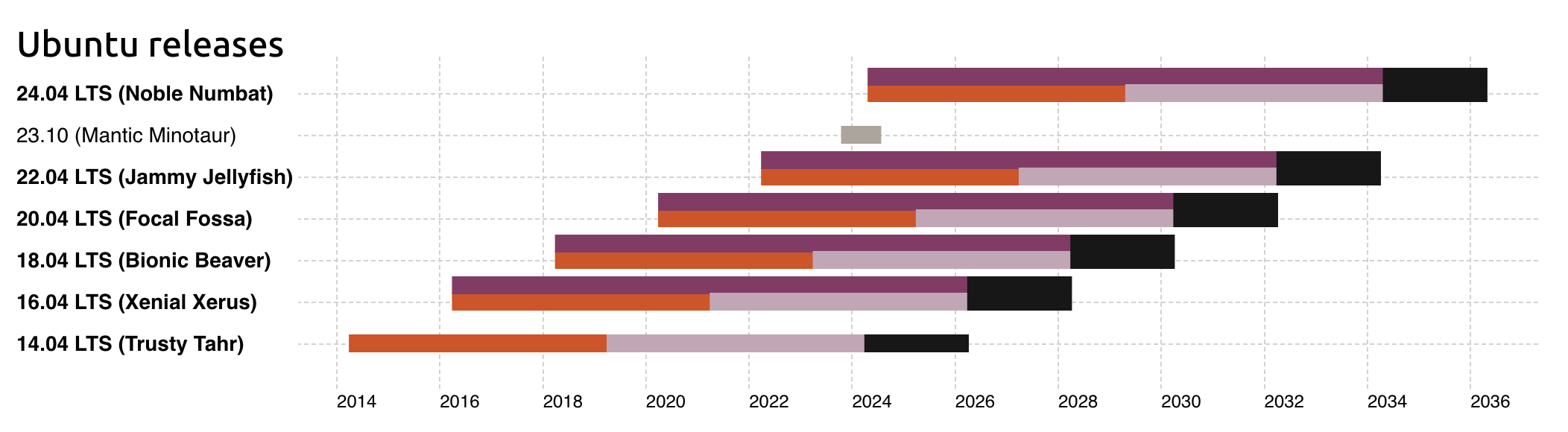

Release Name This refers to the version code name of the distribution, like

focal,jammy, orbullseye. Since repositories host packages for multiple versions, this helps the system pick the right version-compatible packages.

- Repository Components

These define the "category" of software:

main: Officially supported, open-source packages maintained by the distribution organization, in our case its Ubuntu.restricted: Proprietary drivers or software maintained by distribution organization but not open-source.- Other components include

universe(community-maintained) andmultiverse(non-free, legally restricted software).

This format —

<Archive Type> <URI> <release> <components>— is the minimum required to fetch package indexes and install software viaapt.You can extend it further with architecture filters, signing keys, or custom mirror URLs.

Each Linux distribution may use slightly different naming conventions. For more details, check out: Ubuntu repository guide & Debian sources.list reference

Resolving Index

Is deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/ focal main restricted enough to download an index?

Yes. apt constructs specific URLs using the following format to locate and download package indexes: $REPO_URI/dists/$DIST/$COMP/binary-$ARCH/

Here's what each variable means:

$REPO_URI→http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/$DIST→focal$COMP→mainandrestricted$ARCH→ Architecture, machine dependent. Rununame -mto know your architecture.

Putting it all together, apt builds URLs like: https://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/dists/focal/main/binary-amd64. The actual index file is downloaded in compressed formats, typically as:

Packages.gzPackages.xz

We can manually download the index file using wget:

cd /tmp/

wget -q https://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/dists/focal/main/binary-amd64/Packages.gz

gzip -d Packages.gz

ls # You will see the Packages file

Where is the index?

In the previous step, we manually downloaded the index file using wget. But under the hood, when you run apt update, it does the same thing automatically. It fetches the index files from all configured sources and caches the extracted index files in /var/lib/apt/lists/.

This directory contains metadata files downloaded from each source listed in /etc/apt/sources.list. Each file represents an index for a specific component, release, and architecture.

To prove this, let's run the following commands:

docker run --rm -it ubuntu:20.04 # starting a new container in host

cd /var/lib/apt/lists/ # location of index

ls # 0 Files and Folders

apt update

ls # Some Files and Folders

After running apt update, you'll see files like these in /var/lib/apt/lists/:

ls /var/lib/apt/lists/

archive.ubuntu.com_ubuntu_dists_focal_main_binary-amd64_Packages.lz4

archive.ubuntu.com_ubuntu_dists_focal_restricted_binary-amd64_Packages.lz4

# ... and many more files

Here, you might notice .lz4 files locally, even though the server delivers .gz or .xz files. Why is that?

This is because apt decompresses those files and may re-compress them into .lz4 format locally, as lz4 offers much faster decompression, improving performance during package management tasks.

This conversion is a worthwhile trade-off because apt update is typically run periodically, not frequently, so the faster decompression during package management provides a more responsive user experience overall.

You can read this blog where the author compares just how fast lz4 is.

Finally, apt uses these index files to look up for package information.

This is how apt knows that vim is available.

So, apt update has populated our system with package info. But how does that translate into actually downloading vim (or any other package) onto your machine? In Part 2, we'll follow the journey from package index to installed application, revealing the steps apt takes to make it all happen.